60 years of NDT

text: francine van der wiel

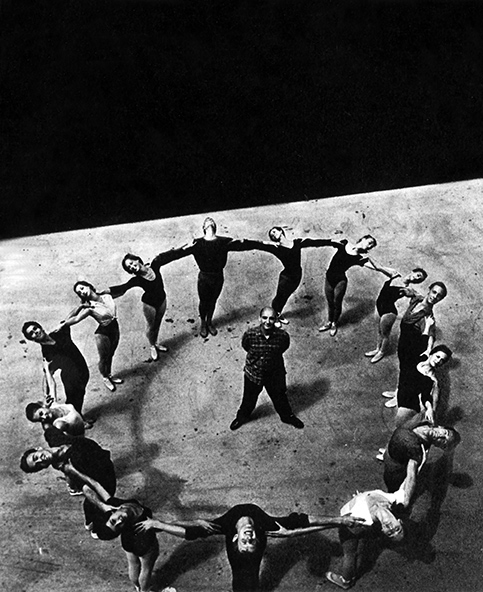

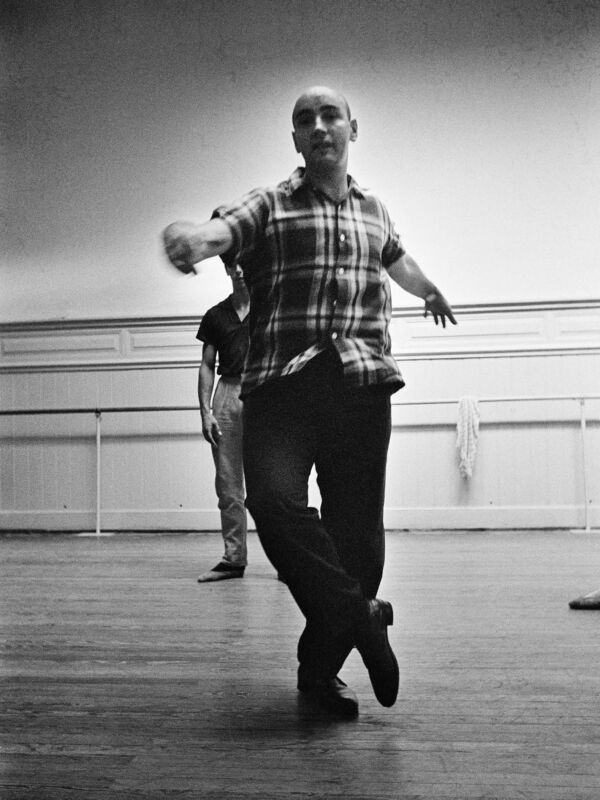

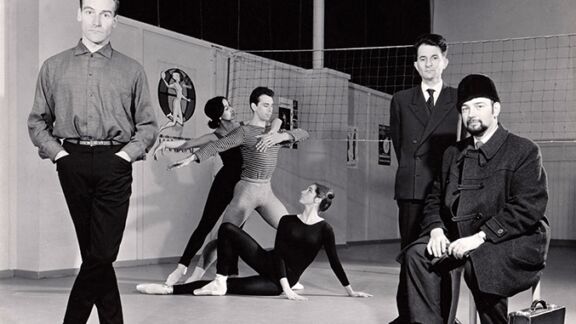

Benjamin Harkarvy played a crucial part in the founding of Nederlands Dans Theater as well as in its first successes. Who was he, and why was he so important?

“I find those circumstances to be of such a nature, that I believe that a new step in the development of the history of dance in The Netherlands can be made.” Benjamin Harkarvy most certainly did not make an understatement when he spoke with a reporter of De Telegraaf newspaper in 1959. But he was right, the brand new Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT) that he had founded with dancer Aart Verstegen and business magician Carel Birnier, would unleash a real revolution in the world of dance, with its fresh, experimental fusion of ballet and modern dance in the years that followed. And he, a heavy set, classically educated American, would prove himself to be of immeasurable value. Still, younger generations don’t know much about him than just his name. “Harkarvy, wasn’t he that fat guy at NDT?” However, ask those who have worked with him about him, and they will sing his praises excitedly. An amazing pedagogue, passionate, a man with an immense knowledge of his field and a clear-cut vision. Someone who wasn’t held back by the constraining traditions of dance would chart an artistic course during the first ten years of NDT in an artistic dual leadership with Hans van Manen and supported by Carel Birnie commercially, that would be copied throughout the world.