Recentering Narratives Project

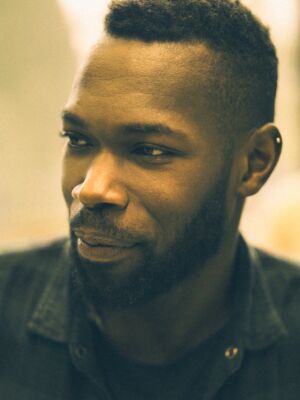

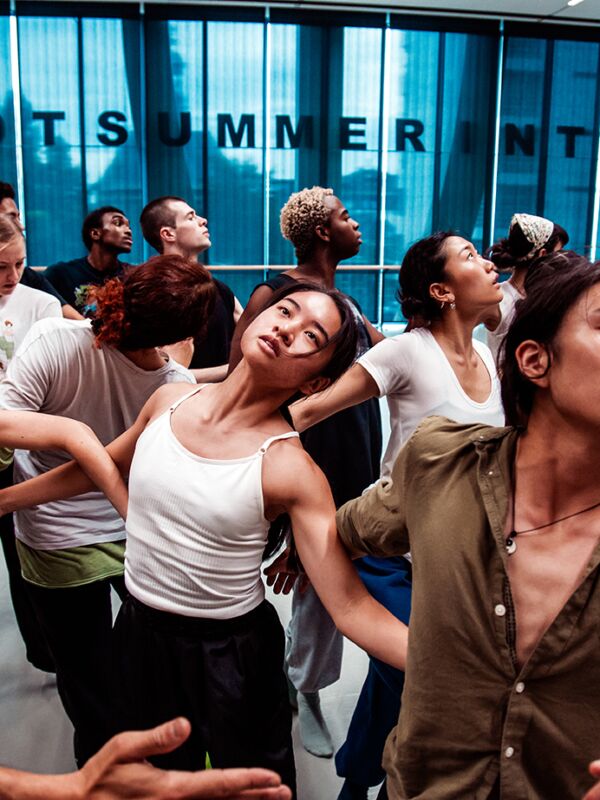

History tends to overlook a wide variety of important figures and stories that never make the canon, nor are stored in our collective memory. With the Recentering Narratives Project, Prince Credell, Policy advisor for Diversity & Inclusion at Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT) is making strides to shed light on these blind spots within the historical context of the company and aims to complement and recover the (NDT) archive with the many multi-racial and multifaceted talents and artists that have graced the (NDT) stage over the decades. This project does not seek to highlight NDT’s past of celebrating differences, but rather wishes to recognize artists of color who have helped carve out the artistic creativity and identity associated with the company and the dance community at large. Through the Recentering Narratives Project the inclusion and acknowledgment of the contributions of these artists will be named and exposed. Not in the least because many of these former NDT dancers continue to contribute vastly to the art form today!

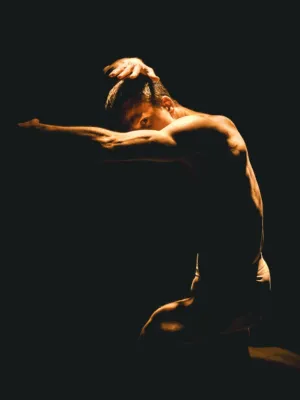

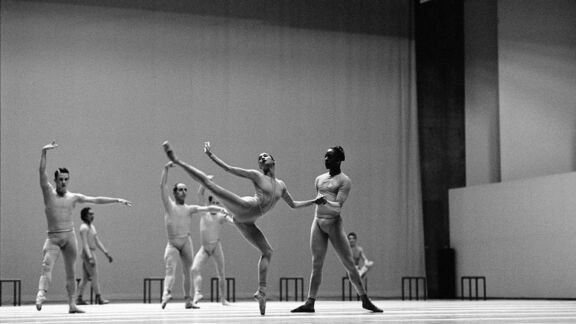

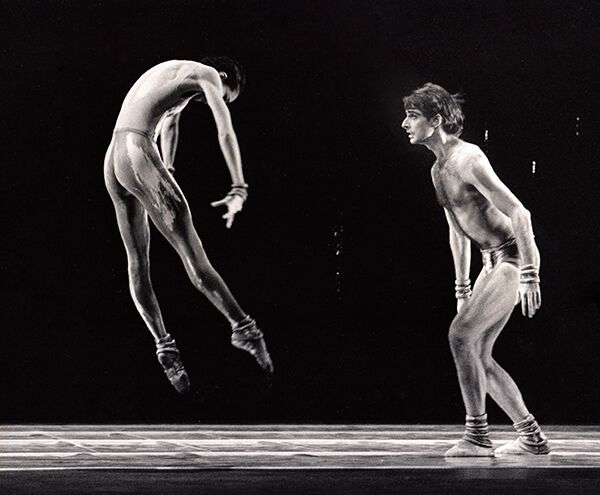

Coverphoto: Stamping Ground by Jiří Kylián. Photo: Jorge Fatauros.